Why sustainability is the heart of the smart city revolution

The smart cities of the future will use tech to lower emissions, cut urban temperatures, and improve quality of life in highly populated areas.

If a printer’s gotten close to your body’s inner workings, it’s usually through a paper cut. But 3D printing is changing that. Organ transplants could involve 3D-printed hearts, tissue grafts might use skin that has been run off using “bio-ink”. And prosthetic limbs have the potential to be custom-printed to fit specific individuals’ bodies – which is a way cooler use of printing tech than batch-producing meeting agendas.

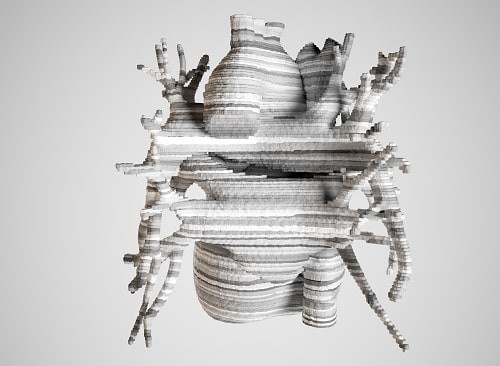

A really awesome potential use of 3D printing in medicine is for organ transplants. For years, scientists have been able to print human tissue using “bio ink”. One ink is “hydro-gel”: a water-based, protein-rich gel. It’s filled with cells and is very similar to our own tissue. By printing it in thin layers that are then bonded to each other, it can be used to create 3D objects like hearts or kidneys.

Since 2014, scientists have also been able to 3D print the blood vessels that allow cells to be linked up to our body’s blood flow. This makes it theoretically possible for a 3D-printed organ to actually survive inside us – so scientists have been trying to make that happen. Chicago’s Northwestern University has 3D-printed artificial ovaries for mice, which were successfully used to give birth. A team from Carnegie-Mellon has created a full-size 3D-printed heart. And replica lungs have even been 3D printed that simulate human breathing by expanding and collapsing when air flows through them.

|

“In the last two years there have been several pieces of seminal work”, says Professor Ruogang Zhao of the University of Buffalo, who is also at the forefront of “bio-printing”, as it’s become known. “This is a very hot field within research.” Professor Zhao’s work has seen the tech take a big leap forward. One of the biggest obstacles to medical 3D-printing is that it can be slow. But in February, Zhao launched tech that sped things up – a lot. He printed a lifesize human hand in 19 minutes – 10 to 50 times faster than the industry standard. As well as looking like something out of Westworld (sped-up video here), the technology now has a patent filed, with the hope that it can be made commercially available. |

|

The use of 3D printing for prosthetics is also shooting forwards. Using synthetic materials to 3D print replacement limbs saved an Australian bone cancer sufferer’s leg after his infected heel was replaced with a titanium version and a plastic skull saved a young Dutch woman’s life. But in the last year, a team at The University of Colorado Denver have pioneered 3D printing complex structures that are similar to real cartilage. Which opens up the possibility of something that 3D-printed prosthetics usually struggle with: replacing the spine. There are, however, still obstacles for 3D printing’s future in healthcare. Professor Zhao thinks that we’re still “maybe 10 or 20 years away from replacing real organs” due to issues with how long 3D-printed organs survive, as well as improvements being needed to the way the artificial blood vessels work. But the future still looks bright. Or in Professor Zhao’s words: “We see amazing things every day that we wouldn’t have thought possible twenty years ago. With the advancement of the field there’s a hope we can produce something that’s fully functional.” |

The smart cities of the future will use tech to lower emissions, cut urban temperatures, and improve quality of life in highly populated areas.

Discover the cities that rank highly for smart city preparedness, and learn why locally relevant innovation is more important than cutting-edge tech.

If you’ve ever thought about becoming a tech investor, read this – learn why investors are the quiet force shaping the future of the industry.

The smart cities of the future will use tech to lower emissions, cut urban temperatures, and improve quality of life in highly populated areas.

Discover the cities that rank highly for smart city preparedness, and learn why locally relevant innovation is more important than cutting-edge tech.

If you’ve ever thought about becoming a tech investor, read this – learn why investors are the quiet force shaping the future of the industry.